Why Measuring Rainfall Is Harder Than You Think

by Kevin Randall | 更新日: 02/17/2026 | コメント: 0

Geoprofessionals (engineers and geoscientists) are increasingly using automated field instrumentation for short- and long-term monitoring of structural health and geotechnical applications. Most are well versed in common subsurface and structural measurements such as pore pressure, water level, temperature, strain, tilt, and extension. Many projects, however, also rely on atmospheric parameters as supporting data (e.g., landslide hazard monitoring informed by rainfall).

In these cases, geoprofessionals are often required to select sensors outside their primary area of expertise and may make equipment decisions based on limited information, while meteorologists are keenly aware of the strengths and limitations of different precipitation measurement technologies. As a result, precipitation—one of the most measured atmospheric variables—is also one of the easiest to mismeasure.

This article focuses on liquid precipitation, the form most relevant to geotechnical and structural health applications.

In this article, we’ll cover:

- How liquid precipitation is measured

- Common sources of error when using standard tipping buckets

- Reducing measurement errors

- Beyond the traditional tipping bucket

- Sensor comparison overview

- Other factors that affect accuracy

How Liquid Precipitation Is Measured

Liquid precipitation has been measured for centuries and can be done using something as simple as a graduated container that is visually monitored or as complex as a laser-based disdrometer to measure droplet size and velocity, among other parameters.

Most precipitation sensors, however, are somewhere in between these two extremes. The most widely used tool today is still the tipping bucket rain gauge, valued for its simplicity, reliability, and low maintenance requirements.

A tipping bucket rain gauge collects rainfall in a screened funnel, directing it into a two-sided bucket mechanism. When one side fills to a calibrated volume, the bucket tips and empties, triggering a magnetic switch, which is recorded by the data-acquisition system (data logger) as a pulse. Each tip (pulse) corresponds to a fixed rainfall increment (commonly 0.01 in. or 0.1 mm). Because the mechanism drains automatically, the sensor can run for long periods with minimal upkeep.

Figure 1 is an example of a tipping mechanism inside a tipping bucket rain gauge. Note how the teeter-totter-style tipping mechanism is housed inside the cylinder directly below the funnel.

Figure 1: Left – external (and top) view of a RainVue™ tipping bucket rain gauge; right – inside view of the RainVue sensor

Modern research has proven that the most accurate way to measure precipitation is to have a buried device in which the catchment area is flush with ground level. In the meteorological community, this is known as a rain gauge pit, as specified by the World Meteorological Organization (WMO).

A WMO-compliant tipping bucket rain gauge pit places the gauge in an in-ground pit with the orifice rim exactly at ground level to minimize wind-induced undercatch. The pit is well drained and covered by a rigid anti-splash grid, with the gauge centered far enough from the pit walls to prevent splash-in. The site is level and unobstructed, with nearby obstacles no closer than at least twice their height above the gauge.

A buried sensor is the most accurate because it measures precipitation without introducing errors that come from using an above-ground sensor. Any sensor installed above ground changes airflow patterns around and over the sensor, causing wind-induced undercatch. This error is just one of two ways in which the tipping bucket rain gauge is prone to a lower-accuracy measurement when compared to a sensor installed flush with ground level.

While pit gauges represent meteorological best practice, they are rarely practical (if ever) for most geotechnical monitoring sites.

Common Sources of Error When Using Standard Tipping Buckets

#1 – Wind-Induced Undercatch

Any above-ground gauge disturbs airflow, leading to wind-induced undercatch.

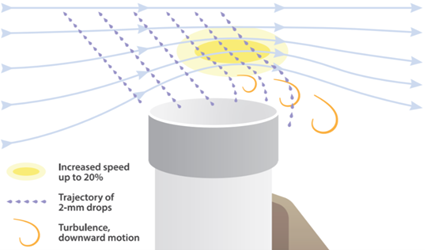

Wind passing around the gauge body creates turbulence and eddies above the orifice that can deflect droplets away from the funnel. Under high winds, this undercatch can be as great as 20%, making this the most significant—and most overlooked—error in liquid precipitation measurement. Even moderate wind speeds can introduce meaningful bias in above-ground rain gauge measurements, particularly at exposed sites.

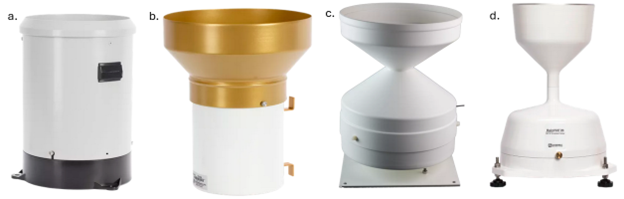

Figure 2 shows a visual summary of the most common tipping bucket rain gauges.

Figure 2: Four common tipping bucket rain gauge shapes – (a) a conventional cylindrical shape, (b) a cylindrical shape with a funnel top, (c) an aerodynamic (plastic) shape, developed at the Institute of Hydrology, (d) an aerodynamic (aluminum) shape, also referred to as calix shape or champagne-glass shape

Figure 3 is an illustration of the impact wind has on a standard cylindrical-shaped tipping bucket rain gauge.

Figure 3: Illustration depicting the gauge-induced impact to raindrop paths for 2 mm drops in 10 m/s (22 mph) wind

Within the world of atmospheric research, two- and three-dimensional modeling have been done to demonstrate the effect wind has on the four common tipping bucket rain gauge shapes. Vertical stream-wise color plots, like those presented by Colli (2018)1, indicate that aerodynamic gauges have a different impact on the time-averaged airflow patterns observed in the vicinity of the collector compared to standard gauge shapes. Colli concludes that aerodynamic gauges mounted above ground catch more rainfall than juxtaposed straight-sided gauges in most instances.

#2 – Undermeasurement during Intense Rain

During high-intensity events, a tipping bucket may miss part of the rainfall due to:

- Splash-out – Water funneled into the tipping mechanism during high-intensity precipitation events is entering so quickly that a non-negligible amount of water splashes out before the tip occurs.

- Water lost during the mechanical tip/reset cycle – While the tipping mechanism is moving from one side to the other (like a playground teeter-totter), a non-negligible amount of water is lost (and therefore will not be measured) before being captured by the calibrated volume available to temporarily store water.

Undermeasurement cannot be eliminated; however, at lower and average precipitation rates, this loss is minimal but grows as intensity increases.

Reducing Measurement Errors

To minimize wind-induced undercatch:

- Install the gauge in an open area away from obstructions that create turbulence.

- Use alter-type windshields.

- Consider aerodynamic low-profile gauges, which reduce airflow distortion (such as the Campbell Scientific RainVue 10 or 20, which will be discussed in greater detail later).

To reduce high-intensity undermeasurement:

- Apply calibration and correction algorithms (more on this later).

- Consider alternative measurement technologies in regions with frequent intense storms.

It is important to understand that these approaches reduce error; they do not eliminate it.

Engineering takeaway: Wind exposure and rainfall intensity matter at least as much as sensor accuracy specifications. If your site is windy or experiences frequent high-intensity storms, sensor selection and installation details become critical.

Beyond the Traditional Tipping Bucket

Tipping buckets remain the standard because they're economical, durable, and easy to deploy. While inherently susceptible to undercatch and undermeasurement, tipping buckets are still viable options for most applications as the known errors can be acceptable for the needs of those applications. Nonetheless, other technologies offer meaningful advantages depending on project needs:

- Weighing gauges – accurate across all intensities and precipitation types

- Optical sensors – no moving parts, good response time, but sensitive to contamination

- Disdrometers – measure drop size and velocity; excellent for research and high‑resolution data

- Acoustic/impact sensors – detect droplet impacts on a surface using sound or impact energy of drops hitting a plate

Many of these are available in heated versions for mixed precipitation, although heating adds complexity and power demand.

A recent advancement is Campbell Scientific’s RainVue 10 and RainVue 20, which use an hourglass-shaped, aerodynamic body to reduce wind-induced undercatch and provide SDI-12 digital output with real-time, intensity-corrected precipitation measurements. The RainVue 10 and RainVue 20 retain the simplicity of tipping buckets while directly addressing two of the most significant tipping bucket limitations:

- The hourglass-shaped body improves airflow around the gauge, reducing the amount of wind forced over the catchment area and increasing precipitation capture in windy conditions.

- While water is still lost during high-intensity events due to splash-out and the mechanical tipping cycle, these losses are compensated for through digital processing that corrects for high-intensity precipitation errors up to 1,500 mm/h (60 in./hr).

Sensor Comparison Overview

To help guide geoprofessionals in selecting an appropriate sensor for different applications, eight sensors are presented below, outlining the sensor type, whether it is heated or non-heated, its strengths and limitations, which use cases the sensor type is best for, and an example of that type of sensor.

Note that while a specific example is provided for each of the eight options, there are a variety of sensors available that are also viable options.

Option 1: Tipping bucket (non-heated, cylindrical body)

- Example: TE525WS

- Strengths: Acceptable accuracy for most applications; affordable, reliable, and low power; easy field deployment; low maintenance

- Limitations: Undercatchment due to air flow distortion around sensor body; undermeasurement due to splash-out during intense rain events. Solid precipitation must melt before it registers. Snow bridging can occur.

- Best for: Off-grid, long-term monitoring in which known limitations are acceptable

Option 2: Tipping bucket with siphon (non-heated, cylindrical body)

- Example: TB4

- Strengths: Ideal for locations where intense rainfall events may occur; contains internal siphon mechanism that causes rain to flow at steady rate to tipping mechanism (regardless of intensity); siphon allows sensor to make accurate measurements over 0 to 50 cm per hour range; more expensive than TE525WS and similar in price to hourglass-shaped gauges; reliable and low power; easy field deployment; low maintenance

- Limitations: Undercatchment due to distortion of air flow around sensor body; siphon incorporated in sensor’s design leading to loss of real-time measurements in favor of improved undermeasurement errors. Solid precipitation must melt before it registers. Snow bridging can occur.

- Best for: Off-grid, long-term monitoring in which known limitations are acceptable

Option 3: Tipping bucket (heated, cylindrical body)

- Example: R. M. Young 52202

- Strengths: Acceptable accuracy for most applications; heating element melts snow and ice for year-round measurements; reliable

- Limitations: Undercatchment and undermeasurement as described above; only for AC-powered applications (high power consumption); undermeasurement due to evaporation from excessive heating (heating should be data-logger controlled [temperature dependent] and used during cold months)

- Best for: Grid-tied monitoring stations in which solid precipitation needs to be registered more quickly than waiting for melt to occur

Option 4: Aerodynamic body tipping bucket (non-heated)

- Example: RainVue 20

- Strengths: Improved capture of precipitation and higher accuracy measurement than standard cylindrical-body tipping bucket; reliable and low power; easy field deployment

- Limitations: Higher cost than standard cylindrical-body tipping bucket.

Solid precipitation must melt before it registers. Snow bridging can occur. - Best for: Windy locations or where high-intensity precipitation is expected

Option 5: Weighing rain gauge (heated and non-heated)

- Example: Apogee Instruments Cloudburst

- Strengths: Accurate measurement across all precipitation types (including snow)

- Limitations: Higher power use when compared to standard tipping bucket rain gauge; high initial cost; high maintenance (not self-draining); must properly dispose of antifreeze; due to size, weighing gauges most susceptible to wind-induced undercatch; use of alter shield highly recommended or is susceptible to significant errors despite technology technically most accurate; snow bridges possible without heated inlet; must remain grid-tied with heating station

- Best for: Research applications; airports; mixed precipitation; easily accessible locations (due to higher maintenance requirement of emptying when full)

Option 6: Optical gauge

- Example: MetSens600

- Strengths: Acceptable accuracy for precipitation sizes at which sensor was tested, lower accuracy thereafter; fast response (no moving parts); works in harsh weather

- Limitations: Sensitive to contamination (e.g., dust, dirt, insects); lower accuracy for total accumulation (inferred precipitation rates based on precipitation size/type and intensity); complex calibration and data interpretation; higher power consumption and upfront cost; not ideal for all climate zones (e.g., drizzle and fine snow hard to detect with consistent accuracy/optics interference with bright sun at low angles)

- Best for: Remote or cold regions, transport corridors; should be considered “precipitation detector” due to accurate measurements across range of precipitation types and sizes

Option 7: Disdrometer

- Example: Zata ZDM100

- Strengths: Can detect rain intensity, droplet size distribution, very light rain; good response time (no moving parts)

- Limitations: High initial cost and power consumption; high level of maintenance (need to keep optics clean, free from obstructions); difficulty distinguishing precipitation versus splash/insects; accumulation totals often less reliable without calibration

- Best for: Hydrology research and urban runoff studies; places where real-time/high-resolution data desired

Option 8: Impact (acoustic)

- Example: Vaisala RainCap

- Strengths: Good response time; no moving parts; good for hail (strong acoustic response)

- Limitations: Acoustic response assumes droplet size (lower accuracy); poor for snow

- Best for: Should be considered “precipitation detector” due to challenges of accurate measurements across range of precipitation types and sizes

Sensor Comparison at a Glance

The table below provides a quick, side-by-side comparison of the sensors discussed above.

| Sensor Type | Example Model | Key Strength | Key Limitation | Best for |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tipping bucket | TE525WS | Affordable, durable, low power | Wind undercatch, splash-out | Off-grid monitoring |

| Tipping bucket with siphon | TB4 | Accurate in heavy rainfall | Delayed response, wind undercatch | Off-grid monitoring |

| Heated tipping bucket | R. M. Young 52202 | Registers snow/ice faster | High power demand | Grid-powered cold climates |

| Aerodynamic tipping bucket | RainVue 20 | Better wind capture and high-intensity corrections | Higher cost | Windy or storm-prone sites |

| Weighing rain gauge | Apogee Cloudburst | Accurate in rain and snow | Maintenance and expense | Research, airports |

| Optical gauge | MetSens600 | Fast response, no moving parts | Contamination sensitive | Remote harsh corridors |

| Disdrometer | Zata ZDM100 | Drop size and intensity detail | Expensive, upkeep | Hydrology research |

| Acoustic impact | Vaisala RainCap | Strong hail detection | Poor for snow | Precipitation detection |

Other Factors That Affect Accuracy

Choosing the right sensor is only part of the challenge. Accurate precipitation data also depend on:

- Placement – Install the sensor at least twice the distance away from an obstruction of height X (e.g., the sensor should be at least 18 meters away from a 9 meter tall tree or building).

- Vibration control – Rigid mounting prevents false tips.

- Leveling – Even small tilt errors can bias readings.

- Power and telemetry – Match battery, charging, and communications to site conditions.

Final Thoughts

While measuring rainfall seems simple, it is important to be aware that there are many options available depending on your specific project needs. For most applications, the standard tipping bucket rain gauge remains a viable option and, if selected, users should be aware of the two inherent errors that are inevitable when using this option: undercatch and undermeasurement.

Measuring precipitation accurately and consistently requires thoughtful sensor selection and careful installation. Whether your project uses a classic tipping bucket, a weighing gauge, or an advanced optical or aerodynamic design, understanding each sensor’s strengths and limitations ensures you capture the environmental context your structural or geotechnical project needs.

Not sure which rainfall sensor best fits your site conditions? Contact our sales team today.

References

1Matteo Colli, Michael Pollock, Mattia Stagnaro, Luca G. Lanza, Mark Dutton, Enda O’Connell, A Computational Fluid-Dynamics Assessment of the Improved Performance of Aerodynamic Rain Gauges. 2018 https://agupubs.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1002/2017WR020549

Credits: Main photo is used with permission from Dr. Stephen Hughes of the Puerto Rico Landslide Hazard Mitigation Office.

Kevin Randall is the Infrastructure Sales Manager for the Americas at Campbell Scientific, Inc. He has worked in multiple markets, focused on not only the North American market, but also the Spanish-speaking LATAM region. Kevin has a bachelor's degree in Geological Engineering and a master’s degree in Hydrogeology. Away from work, he enjoys woodworking, wrestling with his sons, gardening with his wife, and hiking with his dogs and goats.

Kevin Randall is the Infrastructure Sales Manager for the Americas at Campbell Scientific, Inc. He has worked in multiple markets, focused on not only the North American market, but also the Spanish-speaking LATAM region. Kevin has a bachelor's degree in Geological Engineering and a master’s degree in Hydrogeology. Away from work, he enjoys woodworking, wrestling with his sons, gardening with his wife, and hiking with his dogs and goats.

コメント

Please log in or register to comment.